- The 1723 Constitutions

- The Context

- The Protagonists

- Britain, Ireland & Empire

- America

- Europe

- Events & Publications

- Contact Us

Italy, like Germany, was in the eighteenth century a patchwork of independent kingdoms, republics, duchies and the Papal States. Although press censorship was relatively strict and the Inquisition retained influence, there was nonetheless an intellectual climate that was open to new ideas and within the numerous universities and academies and among the educated elites many were receptive to the rational and sceptical ideas advanced by Enlightenment thinkers. And while it might have been anticipated that the spread of Freemasonry in a Catholic country would be constrained, as was the case in Spain and Portugal, this was less the position in Italy.

It is generally understood that Freemasonry was introduced to Italy in the early 1730s and that a Masonic lodge was operating in Florence by 1733, if not earlier. Harry Carr in The Freemason At Work argues that a Lodge in Florence was instituted by Lionel Sackville, Earl of Middlesex (created Duke of Dorset in 1720), without a warrant from the Grand Lodge of England, something borne out by John Lane’s Masonic Records. And following its success, other Lodges were established in Milan, Verona, Padua, Vincenza, Venice and Naples.

A significant factor behind Masonic expansion in Italy may have been the relatively large numbers of British aristocrats on the Grand Tour. The publicity that this generated and the manner in which the Craft was spreading elsewhere in Europe among the elites, especially in France, and the initiation of the Duke of Lorraine (later the Duke of Tuscany) in 1731, underlay Pope Clement XII’s decision to issue a Bull against Freemasonry in 1738. The stated objective was ‘to block the broad road that the influence of the Society might open to the uncorrected commission of sin’. The faithful were thus forbidden ‘to enter, propagate or support the Freemasons… or to help them in any way, openly or in secret, directly or indirectly… or to be present at any of their meetings, under pain of excommunication.’

Some consider In Eminenti and later papal Bulls to be a continuation of the Counter Reformation. After all, Freemasonry, in the eyes of the Catholic Church, was a movement developed by Protestant heretics. That it appealed to both Protestants and Catholics, and to other faiths, and had a growing membership, was of concern given that its approach to religion marginalised the role of the Catholic Church as the only pathway to spiritual redemption.

From Rome’s standpoint, Freemasonry had to be curtailed or – at a minimum – Catholics should be prohibited from joining the organization given that it accepted members from all faiths and required only a belief in a Supreme being. That the ban was widely ignored in Italy, even after the second papal Bull in 1751, suggests that Freemasonry’s Enlightenment tenets and fraternal sociability had garnered widespread appeal.

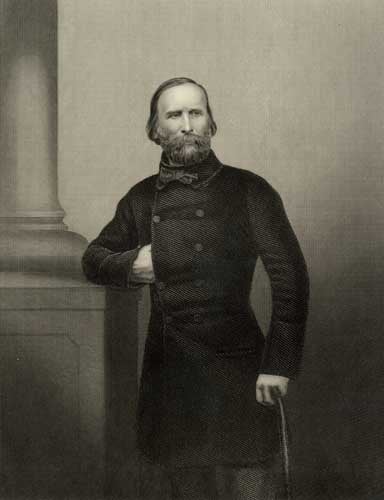

As a footnote, it is interesting to note that the unification of Italy (bar the Papal States) was completed in 1860/61 under the leadership of Giuseppe Garibaldi, an Italian nationalist and Freemason who had previously fought in Latin America in favour of democratic republicanism. Garibaldi was initiated into Freemasonry in L’Asil de la Vertud Lodge in Montevideo in 1844 and came to see Freemasonry – stripped of its more esoteric elements – as a network that could unite progressive liberal men as brothers, nationally and internationally. In 1862 Italy’s Supreme Council of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite, a forum for Italian Freemasons with radical republican views, made him Grand Master. Two years later, the Grand Orient of Italy convening in Florence also elected Garibaldi Grand Master; he served one term in office.

Garibaldi travelled to Britain in April 1864 where his popularity stretched from the masses to the elites. Greeted by adoring crowds, he had an audience with the Prince of Wales and was hosted by the aristocracy, but also met with European exiles.

Freemasons responded positively to his visit. Garibaldi received a deputation from Polish National Lodge, No. 534, led by the artist Sigismund Rosenthal, its Master. The Lodge had been formed by exiled Polish revolutionaries banished during the Insurrections of 1830 and 1846. The Lodge jewel, presented to Garibaldi, is the Polish Eagle mounted on a cross appended to a blue and black ribbon, the colours of the Polish Virtuti Miliari. Garibaldi was also invited to a meeting of Salisbury Lodge, No. 435, in Soho, London, where he was granted honorary membership; it was accepted on his behalf by Giuseppe Basile, a senior member of Garibaldi’s entourage.

Banner Photography © The Old Stables Press